Share:

Hello all!

Have you ever sat in a chair and tried balancing yourself by tilting backwards onto the back two legs of the chair? Perhaps you held onto the table in front of you and used your arms to push yourself backwards to find the balance point? You may remember doing this when you were a child in either grade school or high school. Some of you may have experienced going past the tipping point and having the chair fall behind you, or if you were lucky enough, you quickly recovered by moving your weight forward to prevent falling backwards. (I am not recommending anyone try this while sitting in a chair – it can be dangerous and you can fall backwards and get hurt! I just realize that it is something I have done in my youth and I have seen my own children do it too – and, of course, I cautioned them against it.)

I bring up the example of tilting back in a chair to get us thinking about the effect that displacement of one's centre of gravity can have on tilting and how to apply this when thinking about the different generic mechanisms for tilt-in-space wheelchairs. (Click here for a previous Clinical Corner article on the clinical indicators for using a tilt-in-space wheelchair and pressure redistribution.) This month, we will focus on dynamic tilt wheelchairs and how the mechanism of tilt affects the base of support, including the overall wheelbase of the wheelchair, potential centre of gravity displacement, and the effort required to move a person in and out of tilt.

The first generation of tilt-in-space wheelchairs used a pivot mechanism with gas struts to dynamically move the seated position into various degrees of tilt. In fact, these mechanisms continue to exist today in some models of tilt-in-space wheelchairs. In a dynamic tilt wheelchair with a pivot mechanism for the tilt, there will be displacement of the centre of gravity as the seated person moves through various tilt ranges, just as in the example of pivoting on the two rear legs of a four legged chair. For a dynamic tilt wheelchair with a pivot mechanism, rather than using one's arms to push back on a table to achieve tilt, gas struts, which are activated through a lever mechanism, facilitate the movement.

If we think of the person's centre of gravity as roughly being at the level of the belly button when seated, and we think of the example of sitting on a four-legged chair and tilting backwards onto the rear legs, we can visualize that when upright, the person's centre of gravity is in one position that when tilting backwards, the person's centre of gravity has shifted backwards as the chair shifts backwards. If we draw an imaginary line from the starting point of the centre of gravity to the ending point of the centre of gravity, we can picture the horizontal displacement, or movement, of the centre of gravity. With increasing degrees of tilt when pivoting back on the two rear legs, there is increasing horizontal displacement of the centre of gravity.

If we think about the seat tilting over a wheelchair base, as in the case of a tilt-in-space wheelchair, we need to think about the base of support. The position of the casters and the rear wheels provides a base of support for the seating in a dynamic tilt wheelchair. For a pivot mechanism of tilt, in which there is displacement of the centre of gravity with different degrees of tilt, a long base of support is required to provide stability to the wheelchair so that when it is in the maximum degree of tilt that the system allows, the wheelchair will not tip rearwards.

While a long base of support in a dynamic tilt wheelchair with a pivot mechanism provides stability to prevent tipping when in the maximum tilt range, there can be a compromise to maneuverability. Think of the difference between a limousine and a sports car. It is much easier to maneuver and get into parking spots in a vehicle with a shorter wheelbase than a vehicle with a long wheelbase. In terms of a dynamic tilt wheelchair, whether it is a caregiver pushing the wheelchair or an individual self-propelling, a wheelchair with a shorter wheelbase will be easier to maneuver. In addition, the pivot mechanism means that there will be differences in weight distribution between the front casters and the rear wheels with varying degrees of tilt, which affects the ability to propel and maneuver the wheelchair. (Click here for more information on weight distribution between the front casters and rear wheels, please refer to my previous Clinical Corner article, Centre of Gravity and Manual Wheelchairs.) For these reasons, there have been more developments in tilt mechanisms for dynamic tilt wheelchairs.

The second and third generations of dynamic tilt wheelchair mechanisms sought to reduce the displacement of the centre of gravity through the tilt ranges. By reducing the travel of centre of gravity, the wheelbase of the wheelchair could be reduced, thereby improving some of the maneuverability. The second generation of tilt mechanism used a cantilever, or four-bar-linkage, system, which reduced the amount of travel of the person's centre of gravity when tilted between the neutral position and full tilt of the system. To further reduce the travel of centre of gravity when using the full tilt range, the third generation of tilt mechanisms used a pivot and slide system. With each successive generation of tilt mechanism, the wheelbase of the wheelchair could be reduced, while still providing the stability needed. With a reduced wheelbase, maneuverability was improved.

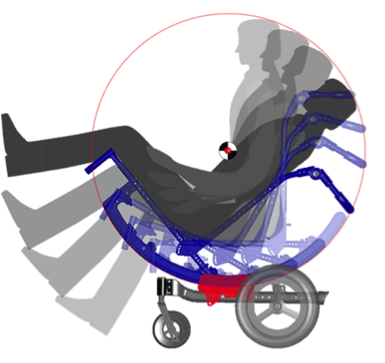

The last generation of tilt mechanism of tilt-in-space wheelchairs is a rotational mechanism. Since the person's centre of gravity aligns with the centre of rotation, there is no displacement of the person's centre of gravity. In addition, gas struts are not required due to the physics of the rotational mechanism. See below for a graphic that illustrates this tilt mechanism.

The small red and black circle in the very centre of the graphic shows the alignment of the person's centre of gravity with the centre of rotation of the tilt mechanism. The shaded areas of the seated person illustrate that whatever degree of tilt the seat is in, the person's centre of gravity and centre of rotation remain aligned. Because there is no horizontal movement of the person's centre of gravity with different degrees of tilt, the wheelbase is shorter, while still providing stability to the wheelchair in different degrees of tilt. (Adjustments can be made to change the anterior/posterior stability of the wheelchair; however, discussion of these adjustments are beyond the scope of this month's article.) With a shorter wheelbase, maneuverability is improved. Maneuverability is enhanced further as the weight distribution remains constant over the front casters and the rear wheels no matter the degree of tilt.

As we have seen, the mechanism of tilt will have an effect on the wheelbase of the tilt-in-space wheelchair, which will effect maneuverability and propulsion of the wheelchair. The other effect that the mechanism of tilt has is on the ease of using the tilt mechanism to bring an individual in or out of tilt. Tilt mechanisms in which there is displacement of a person's centre of gravity, such as pivot, cantilever or pivot and slide mechanisms, means that there may be differences experienced by the caregiver in the ease of putting someone in or out of tilt. For example, if the person's centre of gravity is behind the pivot point, when the levers are engaged to activate the tilt mechanism, gravity will force the system downwards as the person's centre of gravity moves down and towards the back. As the tilt is performed, the person's centre of gravity becomes lower and further away from the pivot point, which increases the reaction. Gas struts are required to provide mechanical assistance; however, the caregiver will still feel the difference in that it can be easier to put someone into tilt when the centre of gravity is behind the pivot point and comparatively more difficult to bring someone up from the tilted position to an upright position.

When the centre of gravity aligns with the centre of rotation, as in the rotational mechanism, because there is no displacement of centre of gravity in different degrees of tilt, there is neutral resistance whether going in or out of tilt. Neutral resistance means that the caregiver will experience that it is equally easy to put someone into tilt as it is to bring someone up to an upright position. This is true no matter how much the seated person weighs. If the caregiver finds that there are issues with either placing the seated individual into tilt or raising the wheelchair from a tilted position in a wheelchair with this tilt mechanism, an adjustment is required to align the person's centre of gravity with the centre of rotation of the system. (Again, a description of this adjustment is beyond the scope of this month's article.)

There is physics behind the mechanism of tilt and understanding the science of the various tilt mechanisms available for tilt-in-space wheelchairs helps us to understand effects on outcomes for individuals who use dynamic tilt chairs and their caregivers. Wheelbase and weight distribution between the front casters and rear wheels and associated maneuverability and potential displacement of centre of gravity and effect on the caregiver's ability to put someone in/out of tilt are all effected by the tilt mechanism of the wheelchair.